December 21, 2018

“Vulnerable” is found frequently in TFFT’s newsletters, on our website, in our notes to our donors and volunteers, and in our blog posts. Vulnerable is heard when we speak about our scholars, written into our vision and mission statements, and scattered throughout our social media posts. We use the word vulnerable as a main descriptor of the population we serve. But what does it truly mean to be vulnerable? How is vulnerability, an emotional state of being, measured and recorded? With the start of a new year, a turn of the page, we thought we would start fresh with clarifying the words and terms we use when we discuss TFFT’s efforts.

TFFT’s use of the Progress out of Poverty Index and Child Status Index are just a glimpse into how vulnerability can be measured, analyzed, and evaluated. The Child Status Index measures tangible items that can be indicators of a child’s vulnerability—things like food insecurity, lack of shelter or clothing, and not being enrolled in school. The PPI is similar, taking into account physical items that make up a family’s wealth. Other markers are not as easy to measure. Is the child loved? Are they happy? Are they safe from abuse, neglect, or exploitation?

The truth is, a vast majority of Tanzania’s population is vulnerable in some capacity. In 2015, the World Bank reported that 70% of Tanzanians are still living on less than $2 a day. Only 28% of Tanzania’s 4.8 million primary students continued on to secondary schools in 2012. Additionally, 60% of high school graduates failed the national educational exam, revealing the ever-worsening state of instruction and support for quality of education in the public arena. When you can’t feed or clothe your children, are you really focused on sending them to school? The nation is experiencing encouraging economic growth, yet remains desperate for strong leaders to help sustain, increase, and utilize this growth to ultimately reverse widespread, devastating poverty.

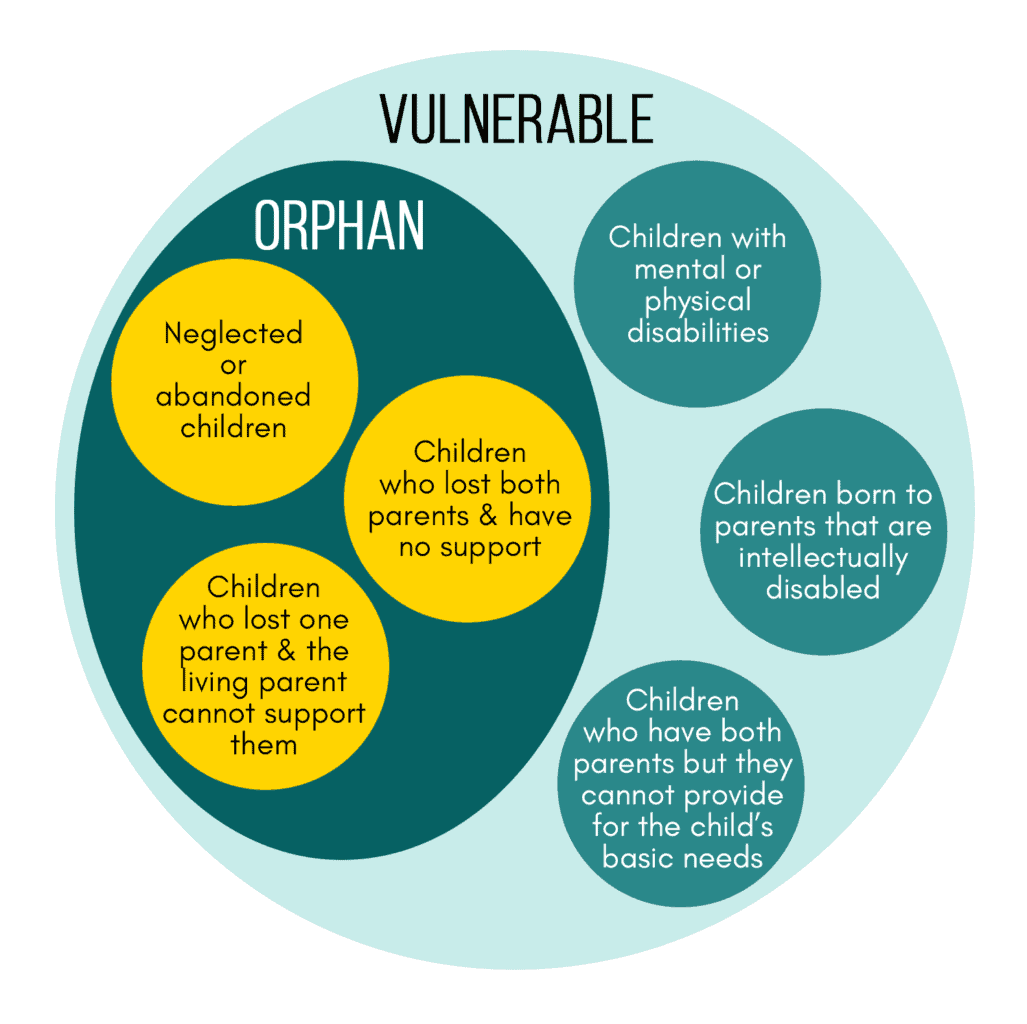

The sphere of vulnerability covers ways in which a child might be vulnerable but not orphaned. According to FHI 360, a human rights NGO based out of NC, “Around 2000, in recognition of the complex ways that HIV and AIDS affects children and communities, development agencies began to shift away from the term “AIDS orphans” to a more inclusive category: “orphans and vulnerable children,” or OVC (USAID, 2000; World Bank, 2004). The term “vulnerable” was introduced as a category in its own right to describe children who were, for various reasons not limited to orphanhood, at risk of harm.“

Naomi, one of TFFT’s newest scholars, is an example of this. Naomi lives with her father, mother, her father’s second wife, and her 10 siblings in a boma. A traditional boma is similar to your block or cul-de-sac, made up of multiple homes that create a community. The family’s home is a mud hut that is well kept and roofed with iron sheets. Naomi’s father works as a guard at an estate, acting as the sole breadwinner for the large family. Naomi and her family have access to food via the chickens, goats, and cows that they tend to on their property. Food insecurity is not an issue Naomi, but she lives in a very remote environment. This hinders her from accessing quality education and the tools she needs to thrive.

Naomi, one of TFFT’s newest scholars, is an example of this. Naomi lives with her father, mother, her father’s second wife, and her 10 siblings in a boma. A traditional boma is similar to your block or cul-de-sac, made up of multiple homes that create a community. The family’s home is a mud hut that is well kept and roofed with iron sheets. Naomi’s father works as a guard at an estate, acting as the sole breadwinner for the large family. Naomi and her family have access to food via the chickens, goats, and cows that they tend to on their property. Food insecurity is not an issue Naomi, but she lives in a very remote environment. This hinders her from accessing quality education and the tools she needs to thrive.

Vulnerability will always be a strong indicator of progress, both in TFFT’s work and in the world as a whole. The choice of vulnerability—willingness to share, to love, to open yourself up to new opportunity—is only an option if the burden of vulnerability—poverty, food insecurity, discrimination, lack of access—is removed as a obstacle for struggling populations.